History, Economy in 1950s Louisa County

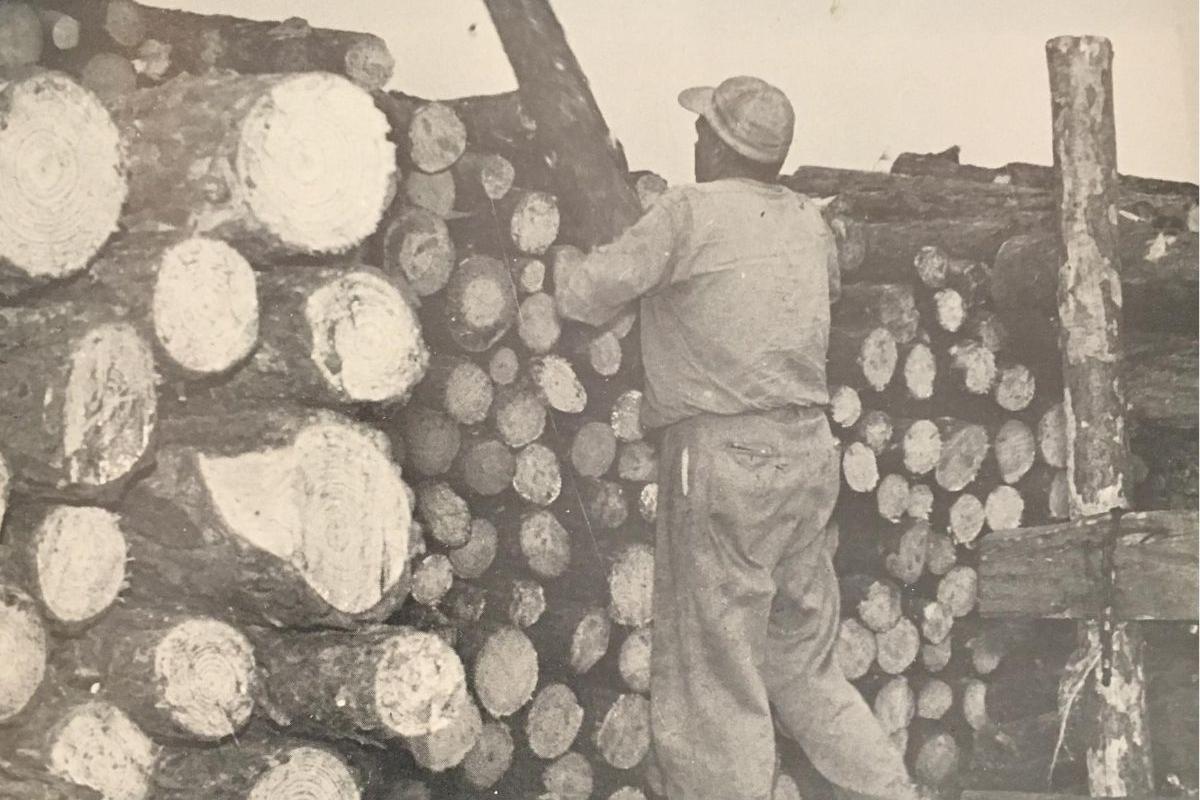

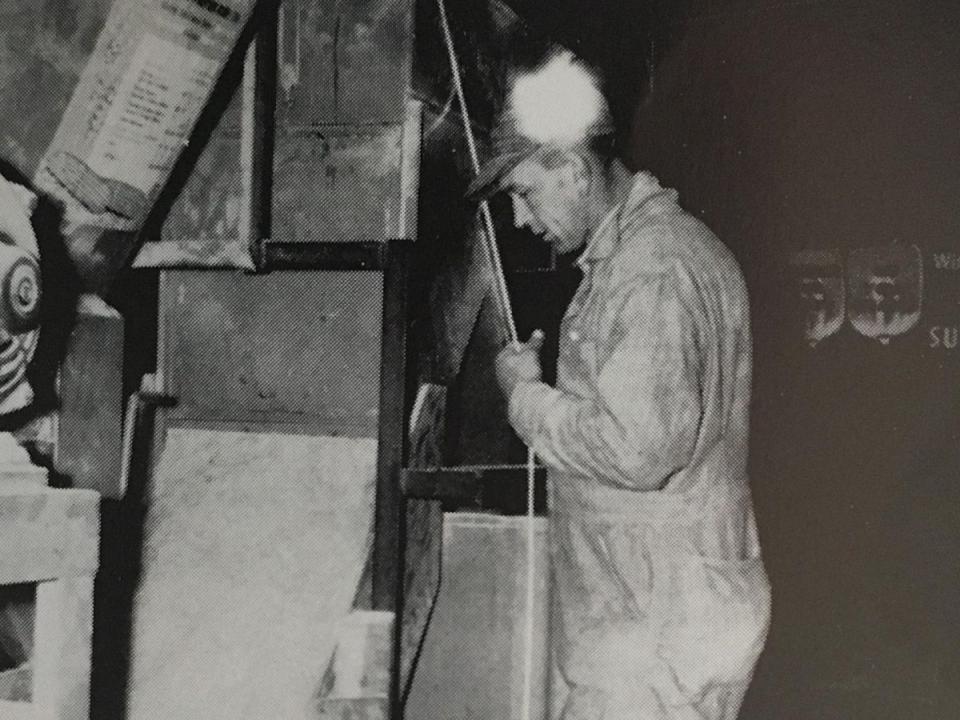

Two industries dominated male employment in 1950s Louisa County. Sixty five percent of males were either farmers or they worked at one of the local sawmills. Many did both. For African Americans, employment was even more concentrated -- over 70 percent worked in these two industries. The industry group “Manufacturing,” which included furniture/lumber/wood construction and sawmill employment, employed 30.9 percent of men in Louisa compared with only 2.7 percent at the national level. Several of our interviewees either worked at a sawmill themselves or had family members who worked at a mill. For example, Annis Mallory’s grandfather owned a sawmill and her dad worked there as well. Ashland Fortune’s father worked at the railroad, sawmill, and ran a lumber business at the same time. When asked about her husband’s employment, Beulah Dymacek responded that he was a “sawmill man.” Finally, Melvin Robinson recalled, “I ended up going to work at 13 [1948] at the sawmill. In ’56, I went to church one Sunday and I was down and out. I didn’t have but a few pennies in my pocket. I said, ‘Is there a better way?’ I thought I would work for myself. I bought a truck and a chainsaw, working by myself. I ended up with logging equipment. I’ve been cutting timber ever since.” Almost all of our interviewees were either related to or friends with men who worked in the manufacturing industry.

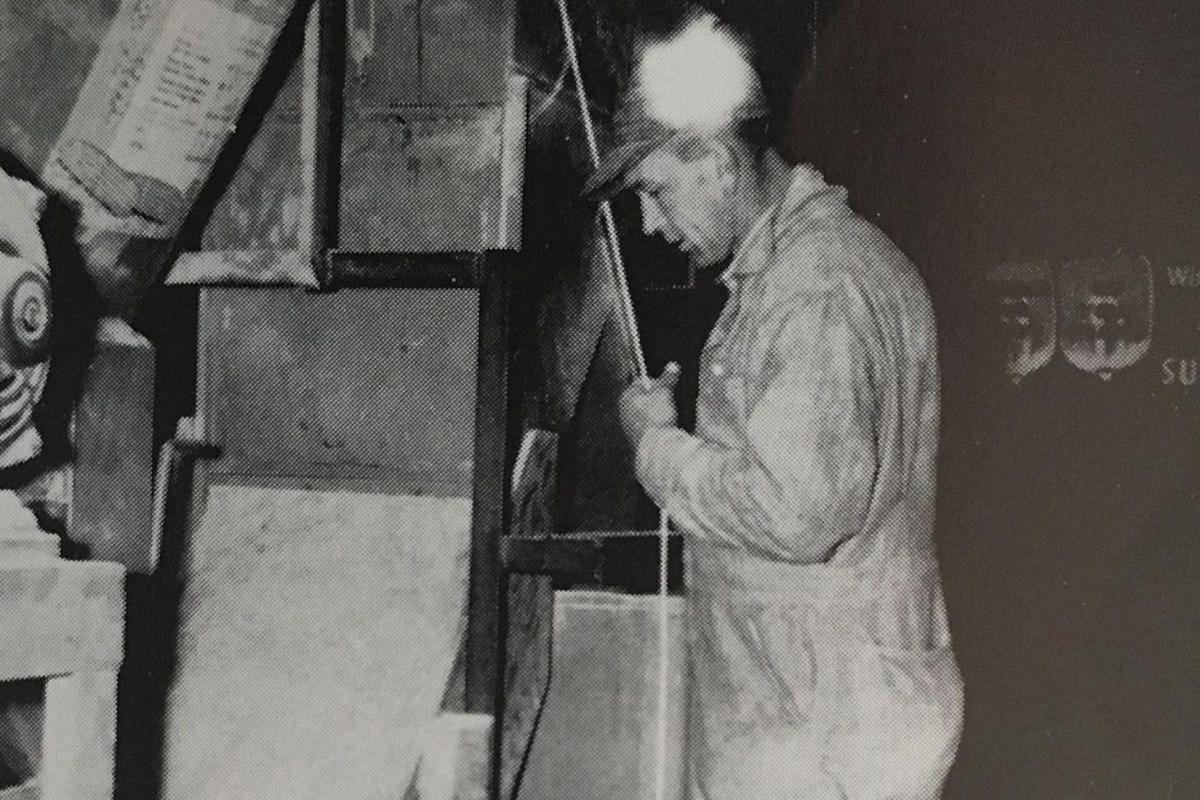

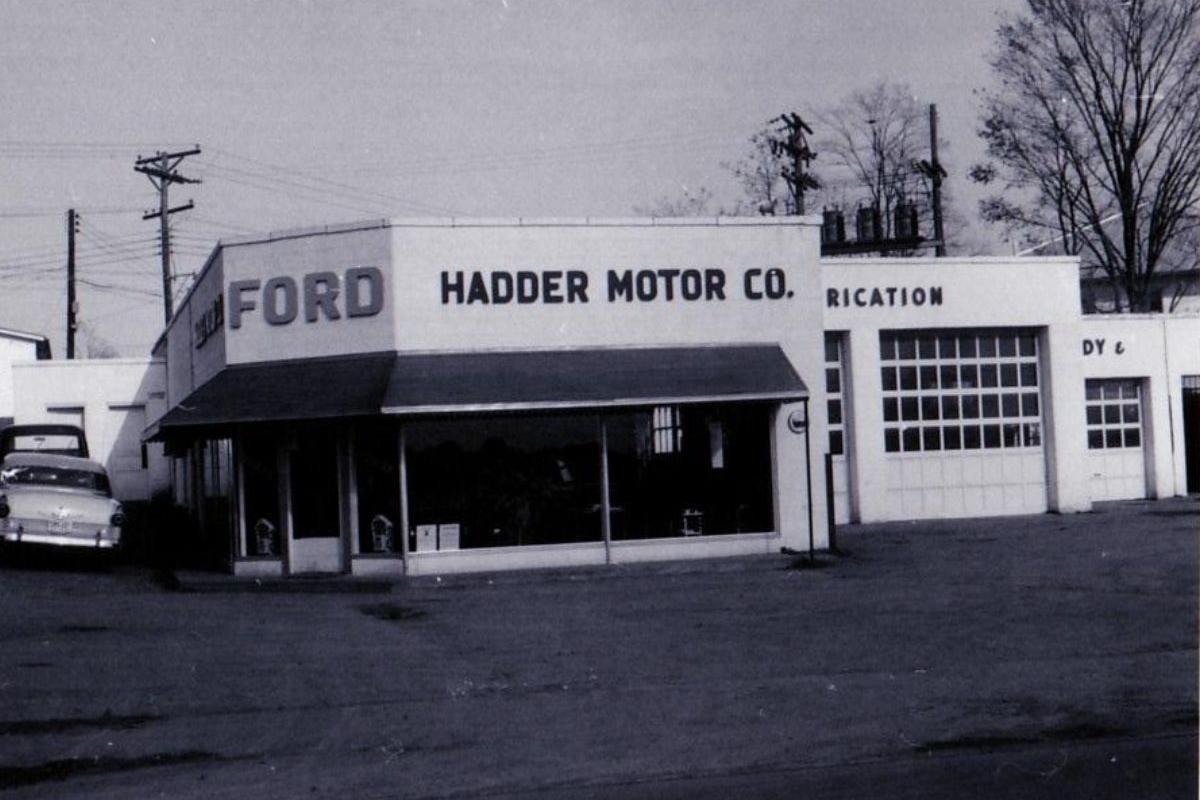

While agriculture and manufacturing dominated Louisa County’s employment sectors, there were certainly men who found employment outside of these two fields. For example, interviewee Ashland Fortune joined the police force when he was 22-years old. He was the town sergeant for 44 years and became sheriff in 1999. Pembroke Pettit’s father was a lawyer. When he came back from WWII, John Thomasson opened a funeral home in Louisa. Louisa County had doctors, dentists, store owners, and teachers. While agriculture and manufacturing were the two main employment sectors, diverse employment opportunities reflected the community’s needs in the 1950s.

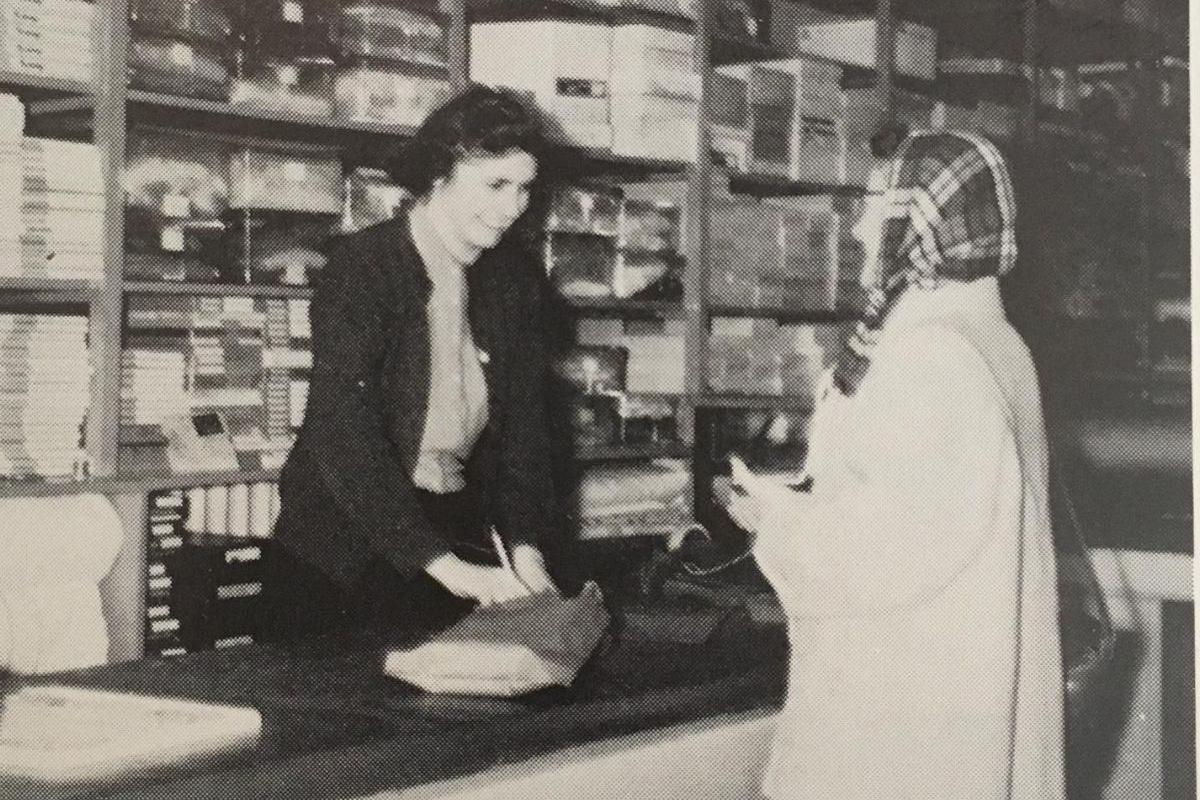

In 1950, about 1 in 10 females in Louisa County were employed outside of the home. Female employment in Louisa was less concentrated than male employment. The largest three industry groups for female employment was manufacturing -- textiles (19% locally vs 3.4% nationally), private household workers (15% locally vs. 9.1% nationally) and education (13% locally vs 6.3% nationally). Blucher Reidelbach said his grandmother cooked at a cafeteria for over 30 years. “The kids would walk from the school to there and she would do all of the cooking and cleaning. Then, after school, my mother and grandmother would clean up the school.” The Woolfolk Textile Factory was a large employer of women in Louisa in the 1950s. However, discriminatory hiring at the local textile plants limited job choice for African American women. In 1950, about 40% of African American women were working in private homes as domestic help.

Homemakers also provided unpaid labor in the domestic sphere. They cooked, cleaned, watched children, did laundry, and helped with family farms. Many interviewees remembered their mothers preparing meals entirely made of food produced on their own farms. As Harvey Fleshman recalled, he would gather eggs, milk cows, and churn butter. His father prepared meat in a smokehouse that was 50 feet from the house, and his mother tended to the vegetable garden. His mother would then prepare meals from this assortment of meat, dairy, and vegetables they grew. This was quite common. Many interviewees recalled going to the store for some essentials, like salt and sugar, but few ever bought vegetables or even meat at the store. Additionally, because Louisa County was rural, many of the technological advances that made doing household chores easier in the 1950s did not come until much later. For example, Homer Robinson, Jr. said his family only had wood stoves in the house. They also had a “ram pump” that used gravity to pump water from a nearby spring to the house, but it rarely worked. Many interviewees recalled not having hot water or even electricity in the 1950s. This meant homemakers had to put it a tremendous amount of time and effort to perform daily household tasks. Their labor, though unpaid, was vital to the functioning of family units in particular, and the county at large.